by Matteo Milani - U.S.O. Project, May 2011

GRM Tools is the result of more than 50 years of cutting-edge research and experimentation at the

Groupe de Recherches Musicales de l'Institut National de l'Audiovisuel in Paris.

These plug-ins were realized by a succession of hardware and software engineers, who formulated the algorithms for the original GRM Tools in the 1990s. Over the years the GRM has focused on developing a range of innovative tools to treat and represent the sound.

The new

GRM Tools Evolution is the latest powerful and imaginative bundle of new algorithms for sound processing. Three new instruments are available:

Evolution,

Fusion and

Grinder. All works in the frequency-domain and provide powerful ways to manipulate audio in real time. I had the privilege of interviewing

Emmanuel Favreau, software developer at

INA - GRM. Here we go!

Matteo Milani: How many people are part of the GRM development team at INA?

Emmanuel Favreau: We are two people, working full-time. Adrien Lefevre handles the Acousmographe. I’m on GRM Tools. We welcome regular students.

MM: Can you tell us a brief history of the GRM Tools from the origin until now?

EF: The first version of the GRM Tools was created by

Hugues Vinet, who is now scientific director of IRCAM in Paris. This stand-alone version offered a couple of algorithms, using the Digidesign SoundAccelerator/Audiomedia III card. The user interface was made with

HyperCard. When I arrived at the GRM in 1994, we took the decision to convert the processing available in the stand-alone version of GRM Tools plugins to TDM for Digidesign Pro Tools III. Treatments were rearranged, some modified, others abandoned. The original GRM Tools Classic bundle dates from this era. Later, the evolution of treatments has been closely following the technological evolution: when the processors became powerful enough for real-time processing, Steinberg introduced the VST architecture and the Digidesign RTAS Pro Tools format. And finally, we developed the ST version - Spectral Transform - when computer processing power allowed us to calculate several simultaneous FFT in real time.

[...] Jean-Francois Allouis and Denis Valette pioneered the hardware development of SYTER (SYsteme TEmps Reel / Realtime System) with a series of prototypes produced during the late 1970s, leading in due course to the construction of a complete preproduction version in 1984. Commercial manufacture of this digital synthesizer commenced in 1985, and by the end of the decade a number of these systems had been sold to academic institutions.

Benedict Mailliard developed the original software for SYTER. By the end of the decade, however, it was becoming clear that the processing power of personal computers was escalating at such a rate that many of the SYTER functions could now be run in real-time using a purely software-driven environment. As a result, a selection of these were modified by Hughes Vinet to create a suite of stand-alone signal processing programs. Finally, in 1993, the commercial version of this software, GRM Tools, was released for use with the Apple Macintosh.

The prototypes for SYTER accommodated both synthesis and signal processing facilities, and additive synthesis facilities were retained for the hardware production versions of the system. The aims and objectives of GRM, however, were geared very much toward the processing of naturally generated source material. As a consequence, particular attention was paid to the development of signal processing tools, not only in terms of conventional filtering and reverberation facilities but also more novel techniques such as pitch shifting and time stretching.

[via

Electronic and Computer Music

by Peter Manning]

MM: About GUI - 2DController. What is the origin of this pioneering, intuitive, but simple performer-instrument "link"?

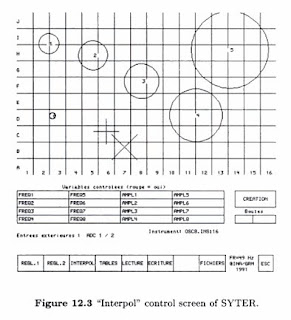

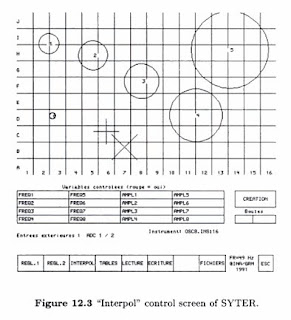

EF: This type of interface has been widely used at the time of SYTER during the 80’s. It allowed us to regain "analog" access to a digital instrument. Indeed, even the manipulation of a slider with a mouse requires some attention (click in the right place, moving vertically or horizontally without mechanical guide, etc.). With the 2D interface, the entire surface of the screen becomes a controller. To obtain a result as soon as you click, the precision of movement is becoming necessary if you want to tune that.

MM: The mapping of parameters on multi-touch control surfaces free us from the use of a mouse and gives us an expressiveness never achieved before. What do you think of this new generation of controllers?

EF: Of course, these interfaces allow an overall and "analog" control which is not possible with the mouse (although the knob 2D mode or "elastic" are possible solutions to overcome the single pointer limitation). Since the engineering of the SYTER we proposed a system of "interpolator balls" to interpolate between different set of parameters arranged in a two-dimensional space. The multi-point control of such a device is natural: we need both hands to shape and transform the space.

"Interpol" control screen of SYTER

MM: Is the SYTER still in use today in Paris?

EF: No, SYTER no longer works. It was composed of several elements (a PDP-11, large hard drives, a vector graphics terminal) which can not be sustained today.

MM: Host-based tools vs. custom DSP engines: will there be a winner or they will continue to peacefully coexist in the business?

EF: For the type of tool that we develop, the winner is clearly the host-based. For very large sessions with dozens of tracks and hundreds of plug-ins, DSP is now the best choice, but they could disappear with the diffusion of multi-core processors.

MM: How long did the Classic Bundle take to get ported from TDM to RTAS?

EF: It's hard to say because it was not done directly. I first made the VST version, and then adapted the RTAS version. The algorithmic part posed no particular problems, the difficulties being rather on the side of the interface between the various plugins and hosts.

MM: How much research was needed to create the Spectral Transform bundle?

EF: The prototypes of the Spectral Transform have been fast enough to achieve. The basic algorithm is the

phase vocoder, which has been well known for a long time. What took time was the interface design, the choice of parameters and their mutual consistency, stability and the whole robustness (i.e. avoid audio clicks and saturation of the values of some parameters).

MM: What's the technology behind the bundles?

EF: If we leave aside the TDM - the processing code is written in 56000 assembly language, all plugins are written in C++. The processing codes are fully compatible between Mac and PC. In addition, the portability of the user interface is guaranteed by

Juce. All development is done on Mac; PC adaptation is virtually automatic and requires minimal work.

MM: A description of version 3 and its new features: what goals have you achieved during this long period of software development?

EF: Having redesigned the interface and rewritten all the code allowed us to add some new features: resizing the window, MIDI control with automatic learning, agitation mode.

Agitation is a generalization of the Randomize, it can be applied to all parameters of random variations in amplitude and frequency control. Now all the GRM Tools are also available as standalone applications. This easily handles individual sounds, to make quick tests and become familiar with the treatments without having to use host daw and sequencers.

MM: How do you manage feedback from musicians and sound designers to improve sound quality and the graphical interface?

EF: The user feedback comes from various forums and from discussions with users and composers here at the GRM. In response to suggestions, plug-ins will be changed, some features will be added (but always in small numbers to ensure compatibility) or it will create a new treatment that may ultimately prove quite different from the original application. This is what happened to Evolution that comes from improving the freeze that can be achieved with FreqWarp.

MM: What are the most efficient methods of applications against piracy?

EF: There is none. Whatever the methods, they will be bypassed one day or another. We must find a solution that is not too heavy for the users, while allowing a minimum of protection. We chose the system of Pace iLok because it is very common in musical applications. The recently announced changes should make it more flexible to use.

Thanks for your time Emmanuel, keep up the good work!

[...] Any transformation, no matter how powerful, will never equal or surpass synthesis, if it fails to maintain a causal relationship between the sound resulting from the transformation and the source sound. The practice of sound transformation is not to create a new sound of some type by a fortunate or haphazard modification of a source, but to generate families of correlated sounds, revealing persistent strings of properties, and to compare them with the altered or disappeared properties.

In synthesis, the formalisation of the devices and resulting memorisable abstraction, offer a stable set of references which can be easily transposed from one environment to another. In sound transformation, no abstraction of the available results is possible and neither is generalisation. The result of an experiment is always the product of an operation and a particular sound to which this operation is applied. The composer must be able to add to the sum of knowledge by reproducing a previously proven experiment.

What makes the wealth and functionality of a system is the assembly and convergence of the whole, its ability at any moment to answer the questions imagined. Specific tools built for a single experiment, no matter how prestigious, are sterile if they cannot be applied to other purposes. - Yann Geslin

References:

[

Digital Audio Workstation

by Colby Leider]

[

sounDesign, a blog dedicated to the world of Sound and Audio Design]

[

On GRM Tools 3, Part 1 - via designingsound.org]

[

GRM Tools 3 review: a classic reborn]

[

The GRM: landmarks on a historic route]

[

GRM's current team]

[

GRM Tools Store]

"Interpol" control screen of SYTER

"Interpol" control screen of SYTER